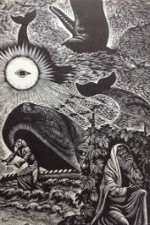

Cover of the 1984 reprint of Fritz Eichenberg’s “Art and Faith” (PH pamphlet #68)

Many useful and exciting meetings have taken place at Pendle Hill over the years. One occurred at a Pendle Hill conference on religion and publishing in 1949, and resulted in a remarkable, forty-year collaboration of art and social action. By the arrangement of Pendle Hill’s Gilbert Kilpack, Dorothy Day, the Catholic pacifist who co-founded the Catholic Worker movement, was seated next to Quaker printmaker and illustrator Fritz Eichenberg.

Through experiences described below, Dorothy Day persuaded Fritz Eichenberg to create illustrations for The Catholic Worker newspaper. Their cooperative work resulted in more than 100 compelling illustrations that inspired compassion and action.

Philip Harnden described their 1949 meeting in his Pendle Hill pamphlet Letting That Go, Keeping This: The Spiritual Pilgrimage of Fritz Eichenberg. The story, related from a different perspective with some different details, is also found in an article by James M. Daprile, Jr. Here are excerpts from the James Daprile article.

“Gilbert Kilpack, a Quaker friend and director of studies at Pendle Hill, called Eichenberg with the exciting news that Day was to be part of a small symposium on religious publishing. Eichenberg was invited and was seated at the roundtable between Kilpack and Day. While Eichenberg was familiar with Day’s paper and her Catholic radicalism and peace efforts, he was overwhelmed by her presence and determination.

“She looked at me wistfully out of her slanted eyes, braids forming a halo around her head. She was clearly made of the stuff of saints and martyrs, although no one realized it then. You couldn’t possibly refuse her anything without feeling ashamed of yourself. She must have known of my work through Dostoevsky whom we both revered. She loved art; I loved her faith and courage.

“‘Would you be willing to do some work for our paper?’ she asked with her bewitching smile. I felt I had been knighted-and hooked! Did she know that I was not a Catholic, just a recently ‘convinced Friend? Yes, she knew and that didn’t bother her a bit….

“Eichenberg and Day had much in common. There was the appreciation for music, love of the great Russian authors Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, a reverence for peacemakers like Jesus, St. Francis, and Gandhi, a social conscience that burst forth in action and art, and an ardent dream that the world was capable of being reformed by compassion and peace.

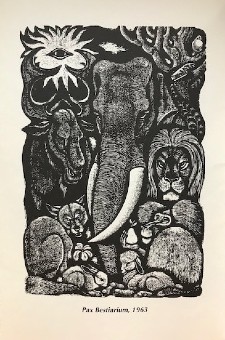

“Pax Bestiarium,” 1963 (c) Fritz Eichenberg (from PH pamphlet #353)

“Day asked Eichenberg for ‘something emotional, some-thing that would touch people through images, as she was trying to do through words.’ Day realized that many of her readers, like the coal mine workers in West Virginia, could not read but could understand through pictures and their allure. This is where Eichenberg and Day created a powerful alliance. Word and image were combined deliberately to promote the tenets of the Catholic Worker movement and to satisfy the conscience cravings of Eichenberg, the Friend.” (Read more of Daprile’s article here.)

Fritz Eichenberg wrote about the influences on his life and art in his Pendle Hill pamphlet Artist on the Witness Stand. He said, “I felt honored that Dorothy Day wanted my work on the pages of The Catholic Worker, a true witness that Art and Faith can go together.”

In an earlier Pendle Hill pamphlet, Art and Faith, published in 1952, Eichenberg expressed his hope as an artist: “The child, the poet, the fool and the saint – how close they are together in their longing for God. The artist is among them and may be allowed to believe that men still prefer beauty to ugliness and deception, blooming meadows to scorched earth, a Bach chorale to the screech of battle.”

For Fritz Eichenberg, art was irrevocably linked to spirituality and conscience. Of the artist’s life as he knew it, he wrote in Artist on the Witness Stand: “To remain sensitive to the human problems surrounding us we will have to descend from our Ivory Towers into the street, perhaps onto the barricades and into a brush with the law. If you are not afflicted with a social conscience this may not be your idea of an artist’s life. But if you are born with certain convictions, your path, no matter how thorny, is laid out for you and you have to follow, even if your tender feet object.”

Today at Pendle Hill, art continues to be linked to spirituality and conscience. The creative process is an integral part of the curriculum of worship, work, and study through which people, in the words of Executive Director Jen Karsten, “engage together in the courageous work of changing ourselves so that we might be the agents of peace that the world needs now.”