By Anna Hill

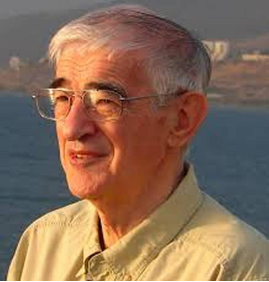

John Dominic Crossan

For scholar and historian John Dominic Crossan, visual and verbal theology “work best hand in hand.” In his view, to privilege one over the other when engaging biblical narratives is to deny ourselves the fullness of the ways we, as human beings, can experience truth in stories. Over the course of Crossan’s online lecture series “Jesus at Christmas: Story, Stone, Evolution,” I and other members of the Pendle Hill learning community have listened to Crossan’s insight into the ways these theologies are intertwined with both our celebrations and interrogations of the Christmas story.

As a Quaker Voluntary Service (QVS) Fellow serving with the education team this year, one of the things that drew me to Pendle Hill was the opportunity to work with lecturers, leaders, and facilitators who are engaging with topics important to me. In the various church communities I’ve experienced, I return again and again to the question of how a practice of reading scripture critically can coexist with spiritual or emotional connections to the church. How can we hold the tension between the two? Part of Crossan’s recent series grapples with just that. I had the chance to interview Crossan, along with a fellow QVS member Jordan Keller and Pendle Hill’s Communications Coordinator Kyle McIver, before Crossan began his series. The interview, along with his lectures, are allowing me to embrace, not shy away from, the coexistence of contradictory truths this Christmas season and beyond.

Crossan’s “Jesus at Christmas” lectures engage both written and visual versions of the Christmas story: the stories of Jesus’s infancy according to Matthew and Luke and their depictions in the Nativity façade of Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia. Can the inconsistencies between the two infancy accounts be reconciled? How can we celebrate Christmas while holding and interrogating the irreconcilable? Crossan’s series looks at this supposed irreconcilability – of image and word, the divergent narratives of Matthew and Luke – as an opportunity for celebration rather than c confusion or consternation.

Crossan constructs a celebration/stone, interrogation/story dialectic and uses the image of a coin to demonstrate their relationship to one another. We physically cannot see both sides of a coin at the same time, and yet one cannot exist without the other: “our vision cannot see the truth” of the coin, Crossan asserts. In the same way, Crossan argues, humans can never truly hold both pieces of a dichotomy. Instead, our urge is to hierarchize. Even in his own attempts at theorizing about dichotomy, he notes himself falling into this trap, saying in our interview: “People will talk about not having a dichotomy, but that’s it – having it or not having it. We are not capable of actually denying dichotomy. All we can do is try and handle it the best we can.” In “Jesus at Christmas,” this means not prioritizing either the visual or the verbal and experiencing the Sagrada Familia and scripture in tandem.

I came to the interview with Crossan with an understanding of image – and by extension, the Sagrada Familia – as a rendering or interpretation of story. To me, the stone was the background “celebration” to the written or oral “interrogation.” I had meant to ask him about how he saw renderings like the Nativity façade as complementing one’s experience of scripture, but with Crossan’s use of the phrase “visual theology,” my understanding of these delineations began to fracture. The images of the Nativity façade, Crossan repeatedly states, are not background noise to an oral discussion about scripture, but are doing theological work in and of themselves. To create a hierarchy and minimize the visual prevents us from embracing image, what Crossan sees as a primary way in which humans can access truth.

The questions I wanted to ask demonstrated this urge to separate the two sides of the coin; I asked about whether interrogation and celebration are intertwined, or whether he is implying celebration necessitates first interrogation of that which is being celebrated, in order for it to be an authentic celebration. But Crossan explains that one can’t come before, after, above, or below the other. Struggling with the interrogation of these concepts, stories, and depictions of the Nativity becomes not a hindrance to the celebration of Christmas, but inextricably linked to it. The celebration of Jesus’s birth, for Crossan, is not done in spite of critical inquiry, but because of it – and vice versa. To interrogate scripture “simply means I want to understand. I want to learn. I want to enter more into what God is telling me.” Only through those questions can we understand the vastness of the mystery and come to celebrate it.

Anna Hill is a member of the 2021-2022 Philadelphia cohort of Quaker Voluntary Service Fellows. QVS is a year-long program during which fellows live in intentional community with one another, engage in spiritual exploration, and serve in a nonprofit. This year, Anna is serving at Pendle Hill with their education team and has supported pamphlet editing and program development, coordination, and outreach. Excerpts from the Pendle Hill interview with John Dominic Crossan are available on Pendle Hill’s Facebook page.